Isolated at home during the covid lockdown, many people reenacted an over 14,000-year-old ritual in their kitchens.1 By simply combining flour and water in jars, bakers awakened the dormant yeast and bacteria clinging to these ingredients, which produce gas and other fermentative molecules that leaven and impart unique flavors in baked goods.

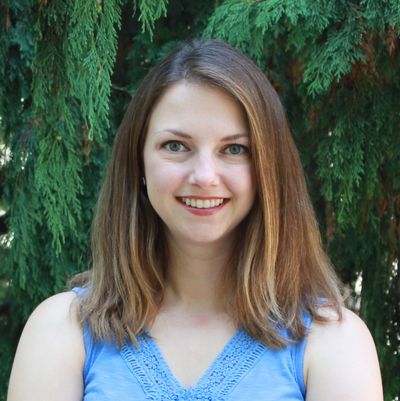

Thanks to pandemic factors including commercial yeast shortages,2 sourdough has seen a resurgence. Bakers experiment in their kitchens and wonder why different fermentation conditions like temperature change the aromatic or flavor profiles of their bread. Researchers like Erin McKenney wonder about the microbial ecosystems responsible for a sourdough starter’s characteristics. “[Bakers] just haven't considered the microbes that underpin that entire dynamic,” said McKenney.

After studying gut microbes during graduate school, McKenney became interested in sourdough as a teaching and research tool when she was a postdoctoral researcher in Robert Dunn’s applied ecology laboratory at North Carolina State University (NCSU). “It’s like a stomach in a jar,” said McKenney. “It's acidic, and it's a simple system [with] high disturbance … You can take it into classrooms in ways that I can never take poop and guts.”

See also “Deleting a Gene Quells a Pesky Cheese-Destroying Fungus”

Previously, McKenney was involved in a project where researchers sequenced sourdough starters donated by bakers around the world.3 Surprisingly, they found that how the starters were made and maintained, rather than the geographic location, affected the microbial populations. To build upon this research, McKenney—now an assistant professor and director of undergraduate programs at NCSU—analyzed the microbes within starters made at the same geographic location and using the same protocol, but fed with various gluten and gluten-free flours. Her team’s work was recently published in PeerJ.4

To produce 40 starters from 10 different flours, McKenney enlisted five middle school teachers who used a learning module that she developed called Sourdough for Science in their classrooms. Their sourdough protocol was based on a common recipe5 and required only basic kitchen equipment and readily available ingredients. “We really needed this project to reflect the processes and practices that bakers are actually using every day in their kitchens,” McKenney said. For ease of use and to minimize waste, they miniaturized the recipe, calling for equal amounts of flour and water by the tablespoonfuls. The teachers refreshed their assigned starters daily for 14 days, measured each starter’s pH and maximum height, recorded aromas, and removed portions for later 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing of the bacterial inhabitants.

See also “Mummified Gut Bugs Reveal Ancient Dietary Secrets”

Before bread can be made, the starters go through three distinct growth phases as they consume nutrients and excrete fermentation products that affect taste, smell, and the microbial populations over the course of 10-14 days.6 McKenney’s team found that one day after starting the experiment, all starters—even those from the same flour type—housed variable bacterial species. During days two through six, the sequencing results showed more lactic acid-producing bacteria in every starter, which lowered the pH in each jar, killing other species that are intolerant to acidic conditions. As the starters reached maturity around day 14, the researchers observed consistent pH readings and other acid-tolerant bacterial species rising to prominence. Aromas changed during the maturation period, with grainy scents wafting out of the starters at the beginning of the experiment, and sour and fruity aromas perfuming later starters. “There are definitely distinctly different bacterial signatures that are associated with these different sourdough starters, based on the flour that they're fed,” said McKenney. This is likely due to differences in the resources each flour provides to the microbes. For example, rye flour produced starters with the highest rise and most bacterial diversity whereas sorghum created the sourest starter.

Different grains and flours might support different bacteria that can completely change your aesthetic experiences when you're eating the bread.

-Erin McKenney, North Carolina State University

“[This work] gives me greater confidence in the benefits of maintaining my three distinct sourdough cultures that are fed three different kinds of flour,” said Eric Pallant, a sourdough expert and professor of environmental science and sustainability at Allegheny College. However, Pallant wondered how stable the tested starters would be beyond the first 14 days. “Flour is not consistent year after year; it's coming from different plants and different forms, in different places. The bacteria in our homes can't possibly be constant,” he said. “So that would be an interesting question.”

McKenney hopes that the results of this study will give bakers a better understanding of their starters and inspire them to experiment with various flours. “Different grains and flours might support different bacteria that can completely change your aesthetic experiences when you're eating the bread,” she said. “It's because the microbes are digesting those flour types to produce different products.” Whether made in home kitchens or used in classrooms as a teaching tool, sourdough experimentation connects modern people to the ancient world.

References

- Arranz-Otaegui A, et al. Archaeobotanical evidence reveals the origins of bread 14,400 years ago in northeastern Jordan. PNAS. 2018;115(31):7925-7930.

- Bakalis S, et al. Perspectives from CO+RE: How COVID-19 changed our food systems and food security paradigms. Curr Res Food Sci. 2020;3:166-172.

- Landis EA, et al. The diversity and function of sourdough starter microbiomes. eLife. 2021;10:e61644.

- McKenney EA, et al. Sourdough starters exhibit similar succession patterns but develop flour-specific climax communities. PeerJ. 2023;11:e16163.

- Hamel P. Sourdough Starter. King Arthur Baking. Accessed November 21, 2023. https://www.kingarthurbaking.com/recipes/sourdough-starter-recipe.

- Harth H, et al. Community dynamics and metabolite target analysis of spontaneous, backslopped barley sourdough fermentations under laboratory and bakery conditions. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016;228:22-32.